By: Rekarius; Asia University

Abstract

Phishing is a cyberattack in which an attacker deceives users by pretending to be a legitimate entity. URL-based phishing attack is a common form of phishing attack, the attacker creating a fake URL that looks like very similar to a legitimate website. Voice phishing, commonly known as vishing, is a technique where fraudsters exploit telecommunication channels to deceive individuals into divulging sensitive information, such as bank credentials, passwords, and per- sonal identification details. This paper discusses an LLM-based method for detecting phishing URLs and voice phishing.

Keywords URL Phishing, Voice Phishing, Large Language Model

Introduction

Phishing attacks manifest in various forms, including email phishing, SMS phishing, voice phishing, and others. Among these, URL-based phishing is one of the most prevalent, typically occurring through email, SMS, and social me- dia. The tactics employed in phishing attacks continue to evolve, ranging from sending fraudulent emails that impersonate legitimate entities to making phone calls that deceive victims by posing as trusted parties to obtain personal in- formation. Voice phishing, commonly known as vishing, is a technique where fraudsters exploit telecommunication channels [1] to deceive individuals into divulging sensitive information, such as bank credentials, passwords, and personal identification details. The growing sophistication of contemporary phishing at- tacks has rendered traditional detection techniques increasingly inadequate, as these methods often struggle to cope with the evolving strategies and deceptive mechanisms employed by attackers. In this paper, we provide a review and discussion on the detection of URL-based phishing [3] and voice phishing attacks using large language models (LLMs) [?].

Methodology

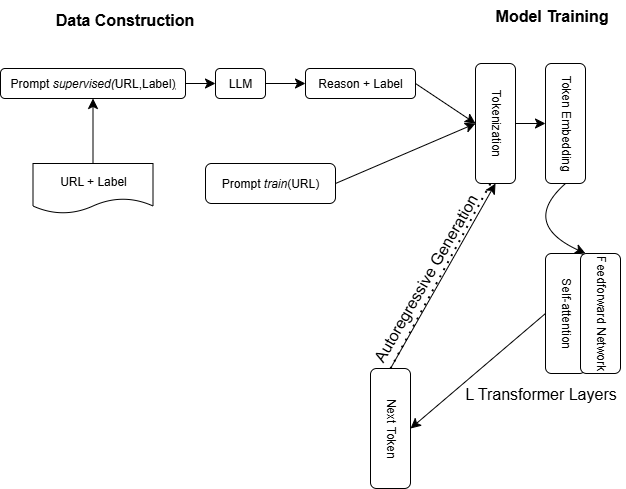

This section is organized into two parts. The first part examines the application of large language models (LLMs) in detecting URL-based phishing attacks, while the second part explores their use in the detection of voice phishing attacks. The schematic diagram of the method is shown in Fig. 1.

LLMs for URL Phishing Detection

The method used in [3] divide into two parts: data construction and model training. The schematic diagram of the method is shown in Fig. 1.

Data Construction

- Prompt Learning: In the context of URL phishing detection, the input data consists of pairs (xi, yi), where xi represents the input sample (e.g., a URL) and yi denotes the label (e.g., phishing or benign). Rather than providing the data directly, each input xi is transformed into a specific prompt, which is a textual representation designed to guide the large language model (LLM) in generating outputs relevant to the detection task. In other words, prompt learning aims to construct explicit instructions that link the input to the task that the model is required to perform.

- Supervised Distillation: Specifically, for each URL and its label pair (xi, yi) in the original phishing URL data, it is first converted into a prompt promptsupervised (xi, yi). Then, they generate explanatory data using a larger generative model:

oi = LLM(promptsupervised(xi, yi)) oi = Reason + Label

- Model Training The original phishing URL data xi is concatenated with the training prompt prompttrain(xi). The new input prompttrain(xi) and the output oi generated by supervised distillation are combined into a training pair (prompttrain(xi), oi). Among them, oi contains the reason explanation and label.

Model Training

The model uses is a pre-trained language model based on the Transformer architecture [2].

- Token Embedding: The subword-based segmentation method is used to divide words into tokens. Each token of the input sequence x = (x1, x2, . . . , xn) is first mapped to a highdimensional vector representation through an embedding layer. The embedding vector is then fed into the stacked Transformer layer.

- Transformer Layer The model stacks L layers of Trans- former, each layer contains two main modules: multi-head self-attention mechanism and feed-forward network. The input of each layer is the output of the previous layer Xl -1 and the output is Xl.

Fine-Tuning

We convert the phishing detection task into a generation task, where the goal of the model is to generate the corresponding reason and label based on the input prompt and URL. In this way, we can fully utilize the capability of the model as an autoregressive language model.

Specifically, the loss function of the model is the standard autoregressive lan- guage model loss, based on cross-entropy loss. The cross-entropy loss calculates the gap between the tokens generated by the model and the target tokens. Let

x = (x1, x2, . . . , xn) denote the input sequence (i.e., prompt and URL), and

y = (y1, y2, . . . , ym)

denote the target output sequence (i.e., the token sequence of the reason and label). Let

P (yt | x, y1, y2, . . . , yt−1) denote the conditional probability of the token generated by the model at step t. The cross-entropy loss function is then defined as:

L(θ) = − Σ log P (yt | x, y1, y2, . . . , yt−1; θ) (1)

m

t=1

where θ represents the parameters of the model, and P (yt | x, y1, . . . , yt−1; θ) is the conditional probability of the model generating the token at step t when generating a sequence.

Figure 1: Schematic diagram of generative phishing URL detection.

LLMs for Voice Phishing Detection

The method used in [1] divide into three parts: LLM-Based Generation and Augmentation of Realistic Phishing and Non-Phishing Call Scenarios, Quantita- tive Evaluation of Naturalness, Diversity, and Detection Difficulty, and Domain- Knowledge Embedded Prompt Engineering for Voice Phishing Detection.

LLM-BASED GENERATION AND AUGMENTATION OF REALISTIC PHISHING AND NON-PHISHING CALL SCE- NARIOS

Case-Informed Generation of Call Transcripts

They generated call transcripts based on 143 real-world case reports obtained from Financial Supervisory Service (FSS). These case cover various types of fraud, including employment scams and family impersonation, and offer rich contextual information such as dialouge flow, impersonation tactics, and psychological manipulation involving urgency or emotional pressure. Situational attributes such as time, location, and impersonated entities were naturally incorporated to reflect real-world contexts. Personally identifiable information was replaced with contextually appropriate synthetic content. To improve the robustness of the model, non-phishing call transcripts were generated that retain the overall dialogue structure and linguistic patterns of phishing calls, but soften key fraudulent components such as explicit monetary requests. These borderline samples, often underrepresented in public datasets, are essential for training models to detect subtle linguistic cues and make accurate predictions in ambiguous scenarios.

Transcript-Based Augmentation of Phishing Call Transcripts

To address class imbalance in existing datasets, data augmentation using authentic voice phishing scripts was perform. Traditional word-replacement methods fail to reproduce the natural conversational flow typical of spoken interactions. To overcome these limitations, they introduce an LLM-based data augmentation strategy that preserves core fraud strategies from real scripts while systematically varying contextual attributes such as time, location, and the identity of impersonated entities.

LLM Prompt Optimization for Realistic Call Script Generation

The initial call scripts generated using a baseline prompt exhibited several unnatural characteristics: (1) uniform sentence lengths, (2) overly structured and grammatically complete sentences lacking the natural variability typical of spontaneous speech, and (3) inconsistent or contextually inappropriate use of honorifics and anonymized entities, reducing overall realism. To address these limitations, we refined the prompts to explicitly enforce variation in dialogue length and response style based on scenario context. immediacy. In contrast, ex- planatory scenarios incorporated longer and more detailed utterances to enhance conversational flow. This strategy resulted in a more diverse and naturalistic distribution of sentence lengths across dialogues. All personally identifiable information (e.g., names, phone numbers) was replaced with synthetic placeholders. Additionally, prompt templates were revised with linguistic guidelines to ensure consistent and contextually appropriate use of honorifics and speech registers.

QUANTITATIVE EVALUATION OF NATURALNESS, DI- VERSITY, AND DETECTION DIFFICULTY

To assess the quality of the generated data, they employ three key evaluation criteria: naturalness, diversity, and detection difficulty. This multifaceted evaluation ensures that the con-structed dataset mirrors more closely real-world conditions, thereby improving its utility for training and evaluating voice phishing detection models.

Naturalness

The naturalness of generated scripts was evaluated using the MAUVE score, to quantify distributional similarity between real and synthetic scripts in embedding space. MAUVE analyzes the global embedding distribution of entire conversations, enabling a contextual assessment of linguistic fidelity. The embeddings were clustered using k-means (k = 500), and the final MAUVE score was calculated using Kullback–Leibler divergence. The score ranges from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating greater alignment with the distribution of real-world dialogues.

Diversity

The lexical and structural diversity of the generated data was evaluated using two complementary metrics, of the generated data using two complementary metrics, Self-BLEU and Compression Ratio (CR). Self-BLEU calculates the BLEU score for each generated sample using all other samples in the dataset as references. By averaging these pairwise scores, Self-BLEU captures the degree of repetitiveness across the generated corpus. Lower Self-BLEU values indicate higher diversity of texts, suggesting reduced redundancy and greater variation in wording.

Compression Ration (CR)

Compression Ratio (CR) evaluates global repetitiveness using a gZip-based compression method. Specifically, CR is defined as the ratio of the compressed file size —compress(X)— to the original file size —X—. A lower CR implies greater diversity, as it reflects fewer redundancies in recurring sequences.

Detection Difficulty

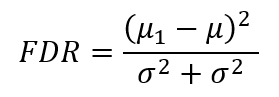

In real-world voice phishing detection, distinguishing between non-phishing and phishing calls is often ambiguous. However, existing datasets typically dis- play clear lexical differences between these two classes, making detection easier than in actual scenarios. To ensure that the generated data include sufficient ambiguous cases, Fisher’s Discriminant Ratio (FDR) and the Silhouette Score (SS) were applied to quantitatively evaluate detection difficulty. Additionally, they proposes Class Centroid Distances Variability (CCDV) as a novel evaluation metric. CCDV assesses the distribution of distances between each data point and all class centroids. This approach enables a more nuanced under- standing of how closely each instance aligns with multiple class centers, offering

deeper insights into detection complexity.

Fisher’s Discriminant Ratio (FDR) quantifies class separability by measuring the ratio of the between-class mean difference to the within-class variance, as defined in Equation eq:FDR. A higher FDR value indicates greater separation between classes and lower intra-class variance, making detection more straight- forward. Here, µ1 and µ2 are the mean vectors of the two classes, and σ21 and σ22 denote their respective within-class variances.

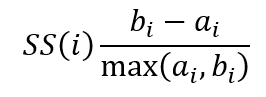

Silhouette Score (SS) Silhouette Score (SS) evaluates how well a sample fits within its own cluster and measures its separation from other clusters. Val- ues near 1 indicate well-separated classes (easier detection), whereas values ap- proaching -1 suggest substantial overlap (more challenging detection). Here, ai represents the average distance between sample i and other samples within the same cluster (cohesion), and bi is the average distance between sample i and the nearest neighboring cluster (separation).

The score is computed as shown in Equation eq:S:

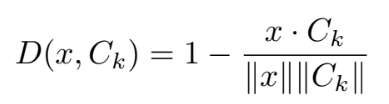

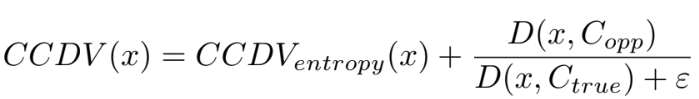

Class Centroid Distances Variability (CCDV) is a quantitative metric de- signed to measure how uniformly an individual data point is positioned relative to all class centroids, while also accounting for the relative proximity to the opposite class centroid. A larger CCDV value indicates a more challenging instance for detection models.

After converting all call scripts in the KorCCVi dataset into KoBERT em- beddings, representative centroids Ck are computed for both phishing and non- phishing conversation data. During this process, the top and bottom 5% of values in each dimension are excluded, and a truncated mean is applied to mitigate outlier effects, ensuring a stable centroid.

The distance D(x, Ck) between a generated data point x and each class centroid Ck is then measured by **cosine distance**, which effectively captures semantic similarity in high-dimensional embedding spaces. This distance is defined as:

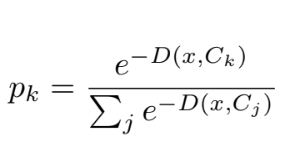

Next, CCDV defines a probability distribution based on distances to each class centroid and employs Shannon Entropy to measure how evenly the data point is distributed across all centroids. This approach allows for a quantitative assessment of whether x is strongly associated with a single centroid or equidistant from multiple centroids. Specifically, the probability pk for centroid Ck is defined as:

where j indexes each class centroid. The set of all pk forms a probability distribution, from which the Shannon entropy is used to compute the CCDV value. The entropy-based component of CCDV is defined as:

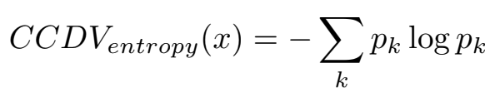

Additionally, to increase detection difficulty for data points that are closer to the opposite class centroid, the **Relative Distance Ratio** is introduced. It compares the distances to the true class centroid (Ctrue) and the opposite class centroid (Copp), as defined:

where ε is a small constant added to prevent division by zero. A higher ratio implies that x is relatively closer to the opposite class centroid, suggesting increased difficulty for detection models.

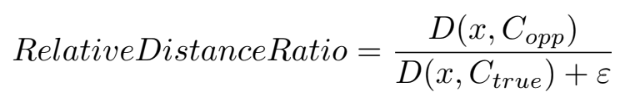

Finally, the overall CCDV value is computed by summing the entropy-based component and the Relative Distance Ratio:

DOMAIN-KNOWLEDGE EMBEDDED PROMPT ENGINEER- ING FOR VOICE PHISHING DETECTION

In this section, they propose Domain Expert LLM, an LLM based detection model that integrates expert knowledge to enhance both the generalization performance and the trustworthiness of voice phishing detection.

-

- Phase 1: Expert-Guided Analysis Criteria Establishment To improve the consistency and trustworthiness of voice phishing detection, we consulted with the expert to define six key analysis criteria, as summarized in Table 3. These criteria were selected for their relevance to phishing detection and their importance and priority were systematically determined. In addition, specific fraud tactics corresponding to each criterion were explicitly outlined to enable more precise analyzes. Less effective criteria were removed and higher priority criteria were placed at the top of the evaluation hierarchy, ensuring comprehensive coverage of a wide range of phishing scenarios.

- Phase 2: Expert Feedback-Based Prompt Refinement The initial prompt for Domain Expert LLM was developed according to the analysis criteria established in Phase 1. To validate the trustworthiness of the detection process and results, the expert examined the reports generated by the model. Specifically, 26 low similarity cases were selected and individual analysis reports were

Table 1: Phishing analysis criteria and selected examples of specific tactics

Priority | Analysis Criterion | Examples of Specific Tactics |

1 | Information Theft Pat- terns | Installation of a fake app after deleting the mobile banking app. |

2 | Monetary Demand Meth- ods | Mentioning terms such as “temporary account” or “secure account” and promising to restore funds. |

3 | Creation of Urgency / Pressure | Legal threats such as arrest and detention. |

4 | Complex Deceptive Tac- tics | Simultaneously leveraging multiple communication channels (telephone, SMS, email). |

5 | Victim Behavior Control and Isolation | Inducing victims to proceed to designated locations. |

6 | Trust Building Tactics | Utilizing victims’ personal information (e.g., from so- cial media or data breaches) to establish credibility. |

generated for each. These reports were reviewed by the expert, whose feedback informed further refinement of the prompt. An important insight gained during this process was the need to clearly distinguish legitimate institutional responses from phishing tactics, particularly in cases involving contact with individuals. Consequently, these responses were explicitly specified, helping the model to distinguish more effectively between legitimate and phishing intent.

Conclusion

Based on this review, it can be observed how LLMs are utilized to transform traditional classification-based phishing URL detection into generation-based detection, by providing both the URL label and the reasoning behind the judgment. In the context of voice phishing detection, the LLM-based framework is employed to enhance the quality of voice phishing datasets and the reliability of detection models. LLMs are leveraged to generate and expand conversation scripts, which are then evaluated quantitatively. They are further used to pro- duce realistic and diverse voice phishing data, thereby addressing scenario bias and class imbalance within datasets. Moreover, LLMs are applied to establish expert-driven detection criteria through the Domain Expert LLM prompt, enabling models to more reliably distinguish between phishing and non-phishing conversations. Additionally, LLMs contribute to the automatic generation of detailed analysis reports and the creation of “unrealized yet plausible” phishing types as training data, thus facilitating the early detection of emerging attack patterns.

References

- Devendra Sambhaji Hapase and Lalit Vasantrao Patil. Telecommunication fraud resilient framework for efficient and accurate detection of sms phishing using artificial intelligence techniques. Multimedia Tools and Applications, 83(41):89111–89133, 2024.

- Ashish Vaswani, Noam Shazeer, Niki Parmar, Jakob Uszkoreit, Llion Jones, Aidan N Gomez, L- ukasz Kaiser, and Illia Polosukhin. Attention is all you need. Advances in neural information processing systems, 30, 2017.

- Bo Zhou and Jia Liu. Generative phishing url detection based on large lan- guage model. In 2025 IEEE 6th International Seminar on Artificial Intelli- gence, Networking and Information Technology (AINIT), pages 1838–1842, 2025.

- Arya, V., Gaurav, A., Gupta, B. B., Hsu, C. H., & Baghban, H. (2022, December). Detection of malicious node in vanets using digital twin. In International Conference on Big Data Intelligence and Computing (pp. 204-212). Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore.

- Lu, Y., Guo, Y., Liu, R. W., Chui, K. T., & Gupta, B. B. (2022). GradDT: Gradient-guided despeckling transformer for industrial imaging sensors. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics, 19(2), 2238-2248.

- Sedik, A., Maleh, Y., El Banby, G. M., Khalaf, A. A., Abd El-Samie, F. E., Gupta, B. B., … & Abd El-Latif, A. A. (2022). AI-enabled digital forgery analysis and crucial interactions monitoring in smart communities. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 177, 121555.

Cite As

Rekarius (2025) LLM-Based Phishing Detection: URL Phishing and Voice Phishing , Insights2Techinfo, pp.1